Taylor Swift, deepfake images, and generative AI regulation: a solution

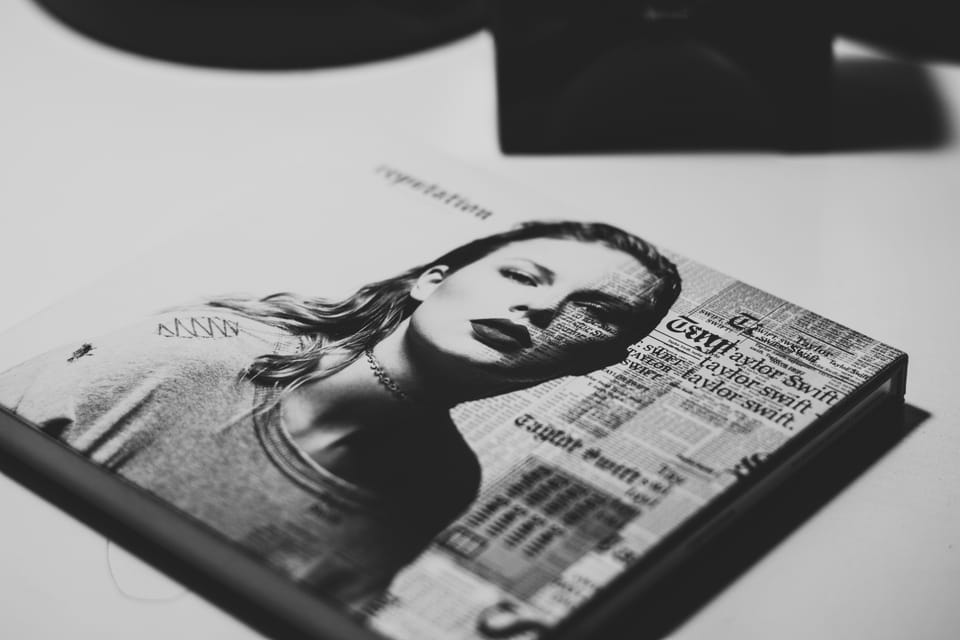

Computers have been generating images autonomously for decades with little interest or concern from the public. This changed last month when deepfake intimate images of Taylor Swift were posted to 4chan, an imageboard website, resulting in a flurry of public cries for generative artificial intelligence (AI) regulation.

The public is half right — regulation is needed — but mountains of new legislation are unnecessary to protect people from the harms caused by people using generative AI irresponsibly. In many jurisdictions, existing tort and statutory law offers protection and recourse to the victims whom the distribution of intimate deepfake images or video has impacted.

Instead, policymakers should consider developing targeted, prescriptive legislation to close gaps in existing legislative and regulatory regimes. A key area of focus could be ensuring adequate deterrents are in place to discourage bad actors from creating deepfakes in the first place. This is easier said than done, but existing regulatory frameworks in the capital markets and anti-money laundering space could provide pragmatic ideas and solutions.

The capability of AI image and video generators has become so advanced that it’s virtually impossible to tell if a particular image is authentic or fake. Generative AI models are a type of deep learning — a software technique using layers of interconnected notes mimicking the structure of a human brain. Unlike traditional AI, which operates based on predetermined rules, generative AI can learn from data and generate content autonomously. The models behind AI image generators are trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet.

Today, the average person can use code-free technology to create deepfake images. Because technical barriers around AI continue to be eliminated, we’re witnessing the democratization of the ability to use AI to cause harm. We’ll continue to see cases like Swift’s in the media. When we do, the impacted individuals will continue to seek recourse and compensation for losses suffered because of how grave the consequences can be. Being on the receiving end of an online attack can have severe impacts on a person’s career, brand, and mental health. In worst-case scenarios, loss of life is possible.

Policymakers will be forced to develop solutions to ensure the public is protected from the harms generative AI can cause; however, that doesn’t mean the wheel needs to be reinvented. For example, in Canada, existing tort law and negligence principles will continue to apply and ensure that individuals creating and distributing deepfake intimate images will be held accountable. Additionally, some Canadian provinces have enacted legislation enabling victims to regain control of their private intimate images that have been shared without their consent.

In British Columbia (BC), new civil legislation protecting individuals from the harms of bad actors covers intimate images, near-nude images, videos, livestreams, and digitally altered images and videos (i.e., deepfakes). Additionally, BC legislation allows the government to hold perpetrators accountable for sharing intimate images without the consent of the individual represented in the pictures or video. What’s more, the legislation requires perpetrators to destroy intimate images shared without consent as well as remove them from the internet if ordered to do so.

While existing and new legislation helps establish protections and clear recourse for individuals harmed by deepfakes, it’s insufficient to deter all bad actors. And once an image or video is uploaded and distributed broadly on the internet, the harm has been done — it’s tough to scrub the internet of a file once it’s out there. What’s needed is a proactive approach to ensure that harmful deepfakes aren’t created in the first place: we need deterrents in legislation to make bad actors think twice before they turn to generative AI to tarnish someone’s name and image.

One solution policymakers could consider implementing is requiring companies developing commercial generative AI solutions to force their users to register with the company and provide government-issued identification for verification by the company before using the companies AI products. Governments and regulators would provide broad oversight of the companies developing generative AI technology, a direction many governments worldwide are contemplating.

In many jurisdictions, the “know your client” requirements described above exist, forcing brokerages and investment dealers to collect basic information about their clients before clients can trade securities or access capital markets. These requirements are in place to deter bad actors from engaging in nefarious activities like fraud and money laundering, which reduce investor confidence in the market and lead to economic inefficiency. Similar requirements could be developed for generative AI companies, resulting in the ability for companies to trace customer activity if needed.

Requiring users to register or obtain a license before using generative AI platforms would help establish accountability and traceability and serve as a strong deterrent to bad actors. Indeed, by collecting users’ personal information and having identifiable information associated with a generative AI platform’s users, it would be easier to track down individuals who misuse technology for harmful purposes. Allowing people to operate in the shadows enables anti-social behaviour and increases the likelihood we’ll continue to see cases like Taylor Swift’s in the media.

Much like bad actors operating in the capital markets, regulating bad actors in the generative AI space will be a challenging game of cat and mouse; logistically and administratively, there are many moving pieces to implementing a regime like this. However, beginning to think about how governments can deter bad actors is essential to the overall process with respect to building an efficient and effective regulatory framework.

Contemplating law and regulation also raises additional questions about accountability and responsibility. For example, what role should a corporation developing generative AI solutions play with respect to deterring bad actors from misusing their technology? I think it’s reasonable to say that companies should not be held responsible or liable for damages their users cause to others, much like Facebook or X aren’t responsible (in the United States), generally, for the content their users create.

However, it may make sense to force these companies to collect basic user information for the abovementioned purposes. Administrative burden is another concern; most governments want to encourage innovation. But generative AI is giving birth to a new software paradigm unlike anything we’ve seen before. Like other activities in society that require registration and licensing where individuals could be harmed, we must at least entertain the question as to whether individuals should have to give up some personal information to gain access to equipment that could hurt others.